Alex Colville

woman_dog_and_canoe_1982.jpg

“It’s the ordinary things that seem important to me.”

nudes_on_shore_1950.jpg

What Drew Me In

As part of my process of understanding Alex Colville, I asked ChatGPT 10 questions I plan to ask of every artist I explore. Here’s what I learned.

Me: What core themes or emotional truths define this artist’s work?

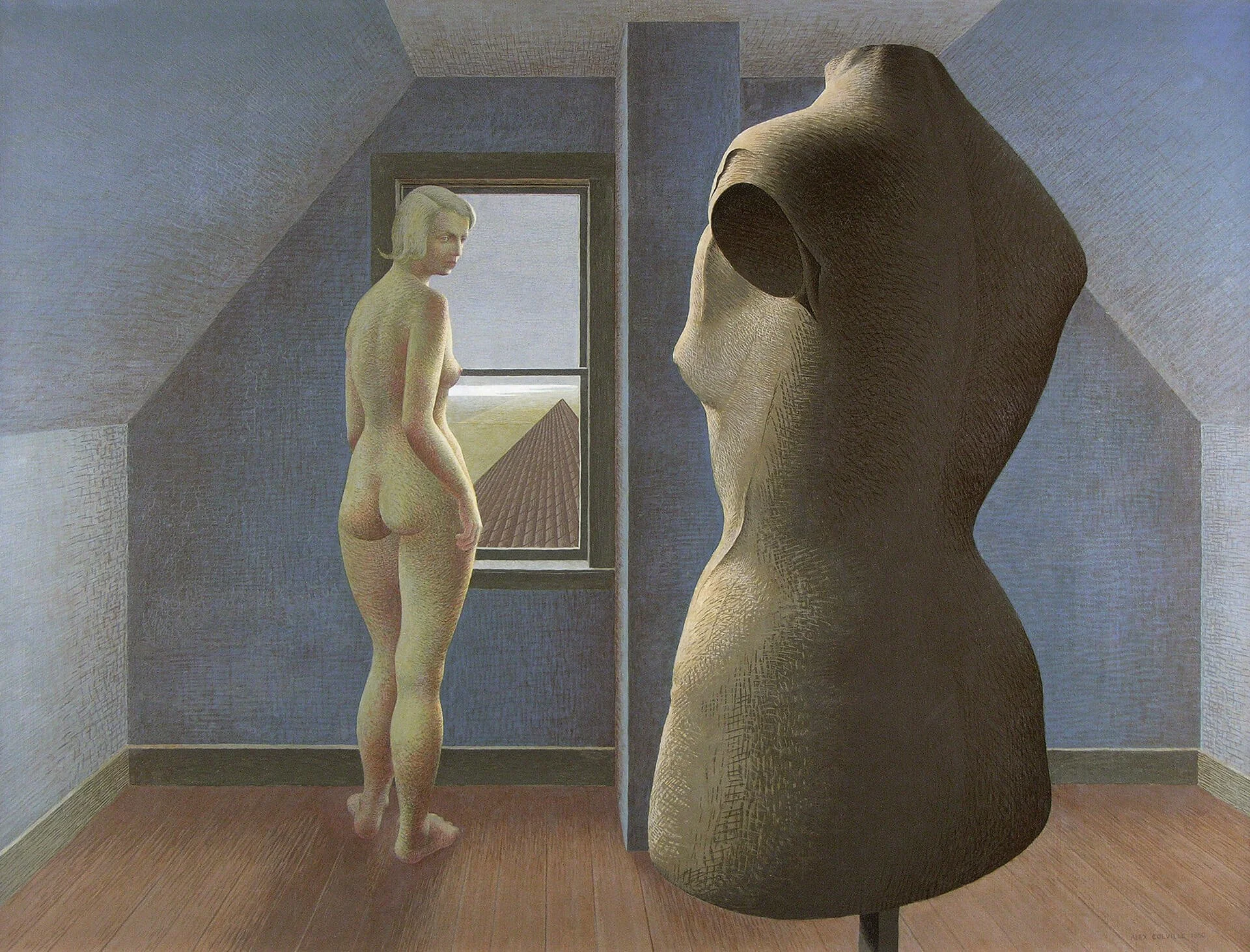

ChatGPT: Alex Colville’s art is deeply rooted in stillness, tension, and the quiet anxiety of everyday life. His paintings often capture the moment before or after something significant — never during — which creates a sense of existential suspense. Themes of mortality, isolation, control, and order echo through his work, yet they’re wrapped in domestic, familiar settings. That tension between familiarity and unease is his emotional signature.

Me: How has their style evolved over time?

ChatGPT: Colville’s style remained remarkably consistent: clean, figurative, and precise. He was deeply influenced by geometry, proportion, and photography. What did evolve was his emotional tone — earlier works feel slightly more observational, while later works become more psychologically charged, especially with repeated motifs of aging, death, and the passage of time. His technical precision stayed, but his inner world grew more prominent.

Me: What personal or cultural influences shaped their work the most?

ChatGPT: Colville’s time as a war artist during World War II had a profound impact. He witnessed death, destruction, and trauma firsthand — and though his paintings aren't overtly violent, the psychological weight of that experience runs under everything. Post-war Canada — particularly the Maritimes — also shaped his vision: quiet towns, open space, routine, and a kind of haunted peace. His wife Rhoda, often his model, was also a huge personal influence — she appears again and again, grounding the emotional depth of his domestic scenes.

Me: What sets them apart in their medium or genre?

ChatGPT: Colville painted in a realist style, but unlike photorealists or traditional academic painters, his work is mathematically composed, emotionally ambiguous, and spiritually loaded. He used precise systems of measurement and perspective, but the result is not cold — it’s eerie, meditative, and uncanny. He bridged the gap between narrative realism and metaphysical inquiry in a way that’s uniquely Canadian but universally resonant.

Me: Which piece best represents their artistic voice?

ChatGPT: Horse and Train (1954) might be the ultimate Colville painting. A lone horse runs headlong toward an oncoming train on a straight track. It’s simple in composition but loaded with meaning — a confrontation with fate, inevitability, or death itself. The tension, the motion inside stillness, the fatalism — it’s all there.

Me: Are there any contradictions or tensions in their work or public persona?

ChatGPT: Yes — and they’re fascinating. Colville’s public image was modest, disciplined, and private. But his paintings suggest a world full of dread, threat, and unease. There’s a philosophical darkness that contrasts with the tidy, quiet Canadian surfaces of his life. Also, though his work is meticulously composed, it’s full of unpredictability — open-ended narratives that resist full interpretation.

Me: What impact have they had on other artists or culture at large?

ChatGPT: Colville’s influence stretches beyond the visual arts. Filmmakers like The Coen Brothers and Stanley Kubrick have cited his work (Colville's paintings even appear in The Shining). Canadian artists and writers have drawn from his tone and themes, and he helped define a kind of modern Canadian visual identity — poetic, restrained, eerie. He carved out space for psychological realism in a cultural landscape often dominated by landscape painting.

Me: What’s one underrated or overlooked work in their catalog?

ChatGPT: To Prince Edward Island (1965) often gets attention—but it's deeper than it seems. Rhoda, seated center-stage, peers through binoculars toward the horizon, while the man sits quietly behind her. This subverts traditional roles: her gaze is active, powerful, focused — and it’s echoed back onto us. Colville challenges us to question who’s observing whom. Critics describe her binoculars as “turning the male gaze back on the viewer,” and describe the painting as an exploration of mutual isolation and connection .

Me: How does their work make you feel?

ChatGPT: Like I’m standing on the edge of something important, but I don’t know what. Colville’s work slows me down. It makes me feel seen and unsettled — like he’s holding a mirror up to the things we bury under routine. It’s a stillness that hums with tension. His paintings don’t let you look away quickly.

Me: If you could ask them one question, what would it be?

ChatGPT: Did painting all that stillness bring you peace — or were you trying to keep chaos at bay? Because part of me wonders whether his obsessive control over composition was a way of containing the existential turbulence he carried from the war — and from life.

Source: ChatGPT

verandah_1983.jpg

What I’ve Learned So Far

As I learn more about Alex Colville, I’m starting to see what his work is really doing, not just technically, but emotionally. His paintings are quiet and minimal, but behind them is a world of control, and trauma, that resonates with me more than I expected. In my own photography, I often find myself removing distractions, simplifying scenes, isolating forms. There’s something calming about deciding what deserves to be in the frame. Maybe that’s what Colville was doing too, trying to make sense of the world, one precise composition at a time.

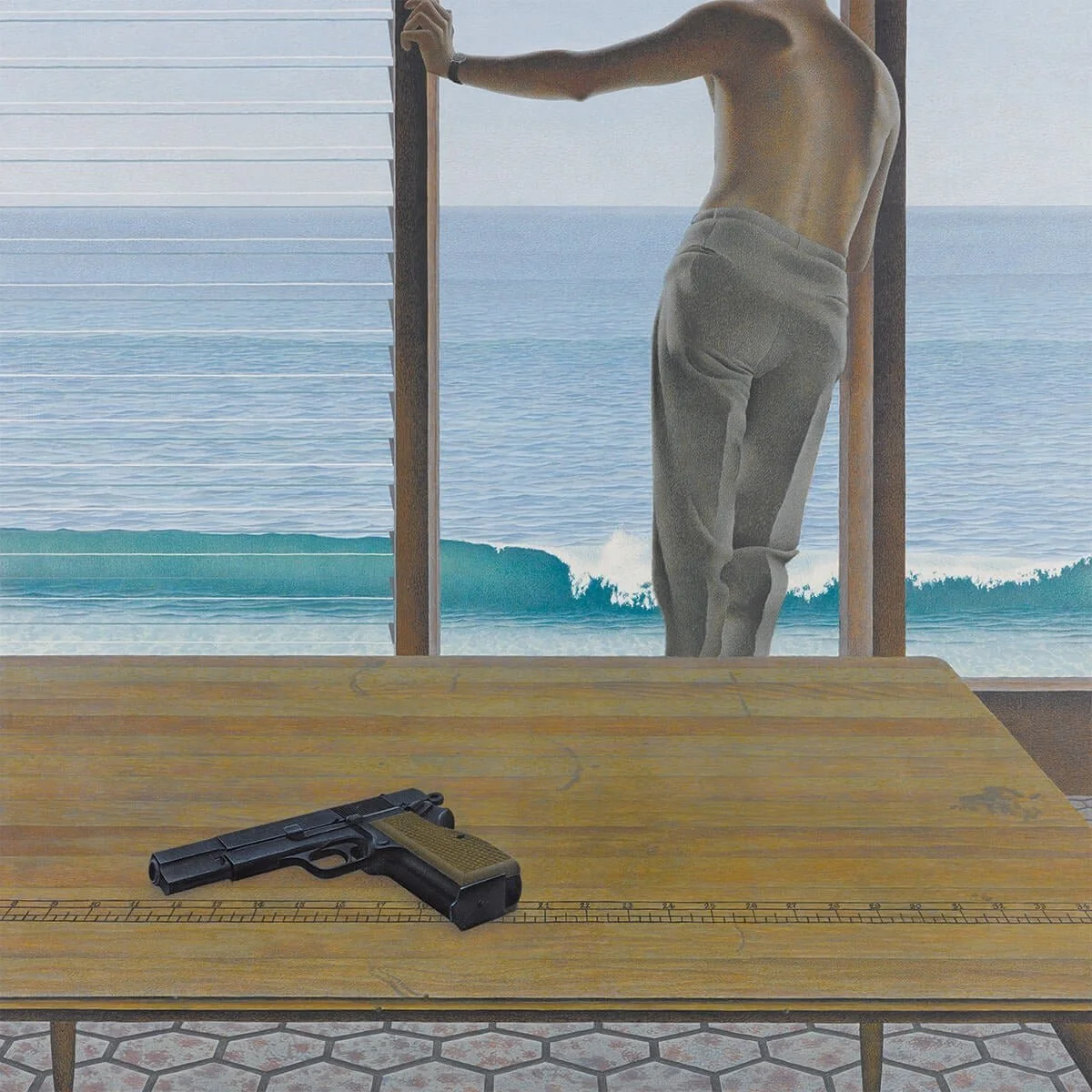

Certain Colville paintings won’t leave me alone. They return at odd moments, when I’m walking alone, or framing a photo, or just sitting still with nothing particular on my mind. Pacific is the one that surfaces most often. At first it seems calm: a man stands shirtless, facing the ocean, the light soft, the scene still. But just behind him, on the table, is a handgun. Nothing in the image moves, and nothing is explained. The tension is quiet but total. That kind of unresolved energy stays with me, it sits in the back of my mind and hums. I think about it when I’m behind the camera, especially when I’m drawn to minimal compositions that feel simple on the surface but carry something unspoken underneath. Pacific reminds me that an image doesn’t need to tell the whole story, it can just hold the space where questions live.

What I keep learning through Colville and through my own photography is that stillness doesn’t mean emptiness. A quiet image can hold enormous weight. In fact, the more I try to simplify a scene, the more I realize I’m not trying to remove meaning, I’m trying to distill it. Maybe that’s why Colville’s paintings stay with me. They don’t shout. They don’t resolve. They just “are” precise, deliberate, unsettling in their calm. And that feels honest to me. There’s so much in life that doesn’t come with answers, that lingers without closure. Why should images be any different?

Even outside his paintings, Colville seemed to understand the quiet power of the ordinary. In 1967, during Canada’s centennial year, he was commissioned to design a special set of coins, everyday objects meant to reflect national identity. Rather than grand or heroic symbols, Colville chose something more intimate, more faithful to his ethos: ordinary animals rendered with extraordinary clarity and dignity. A loon, a rabbit, a howling wolf. It was a quiet portrait of Canada told through the creatures we live alongside but rarely stop to see. It’s a shame those coins are no longer common in circulation. But maybe that’s part of their poetry, they passed through millions of hands, briefly, and then vanished. A moment when art and everyday life truly met, then disappeared like a memory you don’t realize meant something until much later.

I think that’s what I’m drawn to, in the end, the images that stay, not because they explain something, but because they don’t. Colville’s work lives in that quiet space between control and mystery, clarity and ambiguity. And I suppose I’m learning to be okay with that in my own work too. Not every photograph needs to speak in full sentences. Some are just pauses, honest moments of attention, composed carefully, left open. That’s enough. Maybe that’s more than enough.

kiss_with_honda_1989.jpg

Biography Research

Alex Colville, a Canadian painter, and printmaker, born on August 24, 1920, in Toronto, Ontario, emerged as a prominent figure in the art world for his distinctive style and thought-provoking compositions. His career spanned several decades, during which he created a body of work that captivated audiences with its meticulous detail, psychological depth, and a sense of quiet contemplation.

Raised in Nova Scotia, Colville's early exposure to the maritime landscape and rural life greatly influenced his artistic sensibilities. After serving in the Canadian Army during World War II, where he worked as an official war artist, Colville returned to his studies at Mount Allison University in New Brunswick, completing his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1942.

Colville's art career gained momentum in the 1950s when he began exhibiting his works in solo and group exhibitions. His paintings, often characterized by precise details and a narrative quality, defied easy categorization. Colville's style, sometimes referred to as magic realism, combined realism with an enigmatic and symbolic quality that invited viewers to delve deeper into the narratives he presented.

One of his early masterpieces, "Horse and Train" (1954), captures a surreal scene where a black horse stands on a railway track, facing an oncoming train. The tension in the painting, with the horse appearing frozen against the imminent danger, exemplifies Colville's ability to create a sense of disquiet within everyday scenes.

Colville's exploration of ordinary moments imbued with extraordinary significance became a hallmark of his work. His subjects often included family members, pets, and scenes from everyday life, yet he elevated these seemingly mundane moments into profound reflections on the human condition.

The artist's meticulous attention to detail and composition extended beyond his paintings to his works in printmaking. Colville's skillful use of light and shadow, along with his ability to evoke a sense of stillness and contemplation, earned him critical acclaim. His compositions were carefully constructed, presenting a world that, while rooted in reality, invited viewers to question and reflect on the deeper meanings within the scenes.

Colville's career reached new heights in the 1960s and 1970s, with retrospectives of his work held at prestigious institutions like the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. In 1966, he represented Canada at the Venice Biennale, further solidifying his international reputation.

Throughout his career, Colville's art intersected with his interest in philosophy, literature, and the human psyche. His paintings often hinted at existential themes, inviting viewers to ponder the mysteries of life and the complexities of human relationships.

Alex Colville continued to create art well into his later years. His works became highly sought after, and he received numerous awards, including the Order of Canada. Colville's impact on Canadian art was profound, influencing subsequent generations of artists. His legacy lies not only in his paintings but also in his ability to capture the essence of human experience through a unique and contemplative lens.

Alex Colville passed away on July 16, 2013, leaving behind a body of work that continues to be celebrated for its narrative richness, psychological depth, and enduring relevance. His contributions to the art world have solidified his place as one of Canada's most respected and influential artists.

p.s.

According to international standard ISO 8601, monday is the first day of the week. it is followed by tuesday, wednesday, thursday, friday, and saturday. sunday is the 7th and last day of the week.