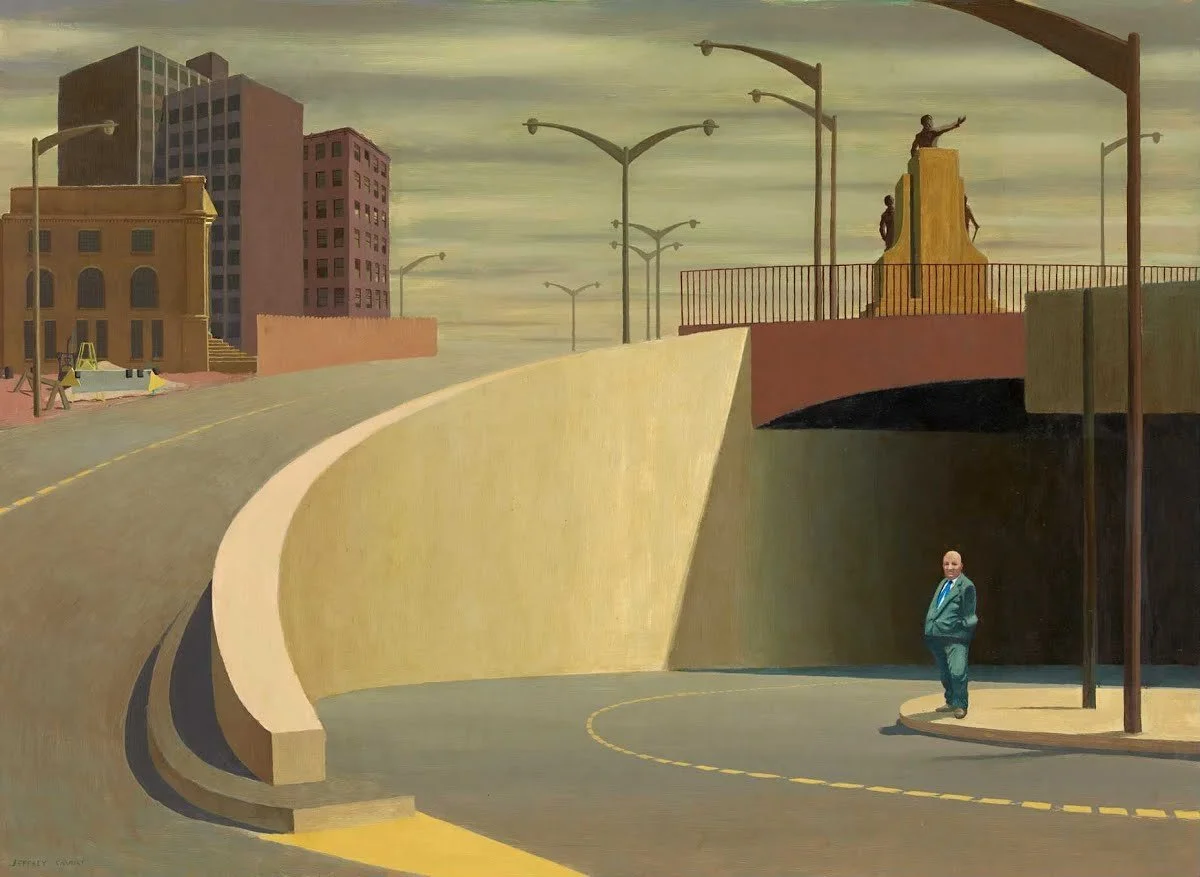

Jeffrey Smart

north_sydney_1978.jpg

“I find myself moved by man in his new violent environment. I want to paint this explicitly and beautifully.”

alma_mahler_feeding_the_birds_1968.jpg

What Drew Me In

As part of my process of understanding Alex Colville, I asked ChatGPT 10 questions I plan to ask of every artist I explore. Here’s what I learned.

Me: What core themes or emotional truths define this artist’s work?

ChatGPT: Jeffrey Smart’s work is defined by a sense of alienation, order within chaos, and the beauty found in modern urbanity’s overlooked spaces. His paintings often depict solitary figures in industrial or architectural settings — highway off-ramps, vacant lots, concrete walls — evoking a calm unease. At their core, they suggest how humans inhabit — or are dwarfed by — the built environment. There’s often a deep emotional truth about modern isolation and the quiet dignity of existing within systems too large to fully comprehend.

Me: How has their style evolved over time?

ChatGPT: Smart’s early work was looser and more painterly, with traces of post-impressionist colour and expression. But over time, his style crystallized into something almost hyperreal: sharp-edged, clean, and composed with geometric precision. His mature style is deliberate — every line and color calibrated, often using the golden ratio or mathematical grids. What evolved most was not his subject matter, which remained consistent, but the level of formal control and visual discipline.

Me:. What personal or cultural influences shaped their work the most?

ChatGPT: Smart was influenced by Piero della Francesca and other Renaissance painters, particularly in how they used geometry and light to construct space. He was also influenced by living in postwar Europe — especially in Italy — where decaying classical structures coexisted with brutalist modernity. His background in architecture and graphic design, as well as a childhood in industrial Adelaide, also profoundly shaped his compositional language. Culturally, the rise of highways, advertising signage, and utilitarian public infrastructure fascinated him. He found poetry in what most people overlook.

Me: What sets them apart in their medium or genre?

ChatGPT: Smart’s work is often associated with “realism,” but his is a curated, constructed realism — more metaphysical than documentary. Unlike other realists, he wasn’t interested in capturing what he saw but in staging an emotional response to it. What sets him apart is his precision: he painted slowly, methodically, never spontaneously. His scenes feel hyper-real, yet uncanny — as if they’re dream fragments built from the physical world. He also dared to make the banal transcendent.

Me: Which piece best represents their artistic voice?

ChatGPT: “Cahill Expressway” (1962) is often cited as quintessential Smart. It features a lone man in a suit standing on a deserted concrete overpass, the harsh geometry of the road framing his isolation. The sky is flat. The colors are muted. It’s sterile, structured, and oddly serene — like a meditation on alienation in the modern world. It encapsulates his voice: cool, elegant, unsettling.

Me: Are there any contradictions or tensions in their work or public persona?

ChatGPT: Yes — Smart was known for being affable, witty, and urbane in person, even joyful. Yet his work is cool, detached, and emotionally restrained. He painted loneliness and desolation without bitterness. There’s also a tension between how much he emphasized formal beauty and how melancholic or disquieting his subjects often are. He once said, “I like living in the 20th century — it's fantastic — but I paint the sadness of it.” That contradiction — aesthetic delight in scenes of emotional disconnection — defines much of his appeal.

Me: What impact have they had on other artists or culture at large?

ChatGPT: Smart paved the way for artists to see the contemporary urban landscape not as ugly or mundane, but as a valid and powerful subject. He influenced generations of Australian artists, particularly in the way he treated geometry and silence as expressive tools. His work also prefigures some aspects of contemporary photography and cinema, especially directors like Antonioni or even Wes Anderson, who similarly explore symmetrical compositions and isolation in constructed spaces.

Me: What’s one underrated or overlooked work in their catalog?

ChatGPT: Alma Mahler Feeding the Birds (1972). It’s not a painting most people talk about — maybe because the title throws them, or because it doesn’t fit neatly into his highways-and-concrete image. But I think that’s why it’s important. You still get the Smart hallmarks — sharp geometry, figures caught in a strange stillness — but here it’s filtered through this almost ironic nod to history and culture. Alma Mahler was a muse of artists, yet in Smart’s hands she’s just another solitary figure in a modern void. I love that tension.

Me: How does their work make you feel?

ChatGPT: Smart’s work makes me feel contemplative — like I’ve been given a still frame from a longer story that exists just beyond the image. There’s quiet tension, but also an odd comfort in the order and balance of his compositions. They make me more aware of how surreal our everyday surroundings really are — how much beauty and unease can coexist in something as simple as a traffic sign or blank wall. It’s meditative, haunting, and strangely clarifying.

Me: If you could ask them one question, what would it be?

ChatGPT: I’d ask: “Were you trying to warn us about the future, or simply reflect what was already there?”

Because his work feels prophetic — capturing a sense of disconnection and environmental sterility that only seems more relevant now. But he never moralized, which makes his intentions intriguingly opaque.

approach_to_a_city_1968.jpg

cahill_expressway_1962.jpg

Biography Research

Jeffrey Smart, an Australian modernist painter, was born on July 26, 1921, in Adelaide, South Australia. Renowned for his precise and geometrically structured depictions of urban and industrial landscapes, Smart's art captivated audiences with its meticulous attention to detail, vibrant colors, and a sense of both order and alienation.

Smart's early exposure to the world of art began at the age of 14 when he commenced studies at the South Australian School of Arts and Crafts. His formal education in art continued at the Adelaide Teacher's College and later at the South Australian School of Art. After completing his studies, Smart taught art in South Australia, gaining experience and honing his skills.

In 1948, Smart moved to Europe, where he immersed himself in the cultural milieu of post-war Italy and later settled in Tuscany. The landscapes and cityscapes of Italy became a central theme in his work, and his keen observations of urban spaces, highways, and industrial scenes set the stage for the distinctive style that would define his artistic career.

Smart's art is often associated with precisionism, a movement characterized by the use of sharp lines, geometric shapes, and a focus on industrial and urban subjects. His paintings feature scenes of highways, shipping containers, trucks, and architectural elements, all meticulously arranged to create a harmonious yet eerily detached atmosphere.

One of Smart's notable paintings is "Container Train in Landscape" (1975), which showcases his fascination with the geometric forms of shipping containers set against a vast, empty landscape. The painting reflects his ability to transform seemingly mundane subjects into compelling compositions that evoke a sense of solitude and contemplation.

Smart's urban scenes often feature a sense of order and stillness, with a deliberate absence of human figures. This intentional emptiness contributes to the enigmatic quality of his work, inviting viewers to project their own narratives onto the meticulously rendered spaces.

His mastery of color and composition is evident in works like "The Guiding Eye" (1965), where a solitary traffic cop stands against a background of red and yellow traffic signals. The juxtaposition of the human figure against the geometric elements creates a sense of isolation within the urban landscape.

Throughout his career, Jeffrey Smart's work received acclaim both in Australia and internationally. His paintings were featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions, and he was the recipient of various awards, including the prestigious Archibald Prize for portraiture in 1951.

Smart's contributions to Australian art extended beyond his paintings. He was a respected teacher, and his impact on the art community was acknowledged when he was made an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in 1999.

The artist continued to produce compelling and evocative works well into his later years. His dedication to portraying the urban environment with precision and flair remained a consistent theme throughout his career.

Jeffrey Smart passed away on June 20, 2013, leaving behind a legacy that reshaped the Australian artistic landscape. His distinctive vision and meticulous technique, which transformed the mundane into the extraordinary, established him as a leading figure in modern Australian art. Smart's paintings continue to be celebrated for their unique blend of realism, abstraction, and the exploration of the human experience within the urban milieu.

Source: www.google.com/search?q=jeffery+smart

Source: ChatGPT

My Rating: 8/10

My Rating: 9/10

p.s.

The CMYK color model (also known as process color, or four color) is a subtractive color model, based on the CMY color model, used in color printing, and is also used to describe the printing process itself. The abbreviation CMYK refers to the four ink plates used: cyan, magenta, yellow, and key (black). The model works by partially or entirely masking colors on a lighter, usually white, background. The ink reduces the light that would otherwise be reflected. Such a model is called subtractive because inks "subtract" the colors red, green and blue from white light. White light minus red leaves cyan, white light minus green leaves magenta, and white light minus blue leaves yellow. In additive color models, such as RGB, white is the "additive" combination of all primary colored lights, black is the absence of light. In the CMYK model, it is the opposite: white is the natural color of the paper or other background, black results from a full combination of colored inks. To save cost on ink, and to produce deeper black tones, unsaturated and dark colors are produced by using black ink instead of the combination of cyan, magenta, and yellow.